On the Painting practice of Jonathan David Westlake Cole by Philip Cole

In the moment where the Turner Prize have shortlisted Project Art Works it seems a good time to revisit the artistic practice of Jon Cole, my younger brother and one of PAW’s founders. Though, the legacy he left with PAW is widely appreciated, his contributions as an artist, teacher, and mentor lack the recognition they deserve.

Here, Kate Adams, who co-founded PAW along with Jon lays out the story of its origins:

‘Whilst sharing a studio space in Hastings, Jon and artist Kate Adams began a conversation about how to enable young people, even those with the most complex needs, to make art on their own terms, within their own, individual sphere of ability. This was a simple proposition but illusive as a motive for making art in collaboration with others. It aimed at a kind of record of engagement through mark making, rather than a way of intentionally making art and yet many of the images made have huge vitality, power and aesthetic balance.’

Jonathan Cole Working with Cherry Lane at Project Art Works Photo Courtesy of PAW

Jon was already in his mid-thirties when that first exhibition, ‘Art Works’ took place at the De La Warr Pavilion Bexhill on Sea. This was a collection of work from school residencies and from workshops for children with severe neurological impairments set up by Kate and Jon in 1995-6. He was then a lecturer on the Foundation course at Hastings college of Art. His commitment and passion, the fluency and originality he

expressed in relation to painting helped shape the practice of many young artists who passed through Hastings College of Art. Rod Harman, Jon’s colleague and dear friend has described Jon and his painting in the following way:

‘A great deal of Jon’s work was in the offing (which is art) - there was a greatness about him. Both in his figurative and abstract work, I feel deeply a disintegrating geometry of shadows and volumes which whelm over me, effect and change me, and make me think afresh. There is of course the ‘Tuscan’ skill, beloved of the academy and profoundly seductive for a person of religious depth. But I think he grew out of this and found an even more mystical and spiritual set of awareness. His work became painted sounds, as if it had been spoken over (consecrated). Little dots, scratches and awesome scales took over, everything that is superfluous was vaporised. Moth wing colours and patterns were set into paint. Looking at the paintings one becomes weightless and able to climb, like Jacob’s Ladder, in a dream.

Untitled (tree) 2006 Oil, emulsion on canvas 167 x 133 cm Courtesy of Marley and Mana Cole

Jon cannot be separated from his effect on people. His work seems to be stirred, forms a surface, allowed to dry, and then reached under. As a teacher he ‘re-surfaced’ human beings - allowed them to rise to their surface, reach into themselves, dive happily into their very being. By the use of his eyes, intelligence, fingertips and palms he rescued many’.

Jon studied painting at Bristol following a foundation year at Ravensbourne College of Art. He then spent three years at the Royal Academy schools. He lived in Hackney, squatting in houses near Victoria Park and pursuing his painting practice alongside other young artists. At this time his painting could be described as expressive and broadly figurative. A move to Hastings coincided with a change in the direction manifested in his solo exhibition ‘The Baptist and the Sea’. As life became more pressured, he pursued his work privately and most often at night. He tended to avoid the mainstream art world, preferring instead to organise independent exhibitions - most notably in Berlin (1996 and ‘98), Mumbai (1998), St Bartholomew’s Church, Brighton (2000), Spitalfields London (2001), Newchurch, Romney Marsh (2002), and The Arches, Hastings (2006).

In 2002 Jon and Caroline LeBreton purchased 12 Claremont, a five-storey Victorian brick and timber warehouse located next to the Hastings library. Subsequently they spent several years developing it into a contemporary and community art space for the town. They transformed the building into studio spaces, a café and two galleries. Jon converted the huge fourth floor level into a studio which he later shared with the filmmaker Tim Corrigan and his sound engineer brother, Marley Cole. The studio windows open out onto a view of the sandstone church and views across the roof tops of Hastings to the castle. The promenade and the pebbled beach and the sea are just beyond the studio door; seagulls make their home on the studio roof. All these things entered into his painting. Once, gesturing outside, he said, ‘Look at the birds, and seeing all this from up here’.

Jon’s subject matter and painting process were always evolving. His earlier works had biblical themes. Our father was an itinerant preacher and as a child and adolescent Jon would accompany him on his preaching excursions. The story of John the Baptist fascinated Jon and he came to identify himself with him – and not just because of their shared name. Although popular and gregarious, Jon felt himself to be an outsider and, after all, the Baptist was a rugged prophet, an outsider with a message and vocation. Whilst at the academy Jon sometimes slept rough in a small BT shelter he found in Green Park. There were connections there, a desire to live on the unsettled edge of things. In the statement for his exhibition at the Royal Academy schools, Jon wrote:

‘The source of the paintings are mainly biblical. The myth of John the Baptist has greater secular resonance than Christian relevance. He is at the end of an accelerating chapter in history which marks the Christ. The penultimate prophet in the wilderness making clear the way; for the notion of spiritual rebirth. A proclamation, his self, rock and no water and the sandy road, which history has rewarded a new myth of potent male sexuality. Joachim; a cry of dire portent. I have been concerned in these pictures for his mother.’

Refugee Status 1986 – 89 Oil on canvas 103 x 77 cm Courtesy of Philip Cole

Mother and Child 1989–93 Oil on canvas Size unknown Courtesy of the artists estate

Jon was committed to the idea that painting and being a painter was a natural vocation. He came to reject the traditional faith of his youth along with its trappings and teachings. And yet, nonetheless, he wrestled with the need for a core belief, a ‘Spiritual way’ to help him to navigate. Painting was the vehicle in which he would make that journey. In the statement for ‘The Baptist and the Sea’ he affirmed:

'Painting has become my way in life. I have concentrated on this more than anything else.

'When I was young, I thought life would be acceptable if one had an obsessive vocation. At first, I thought I would be a missionary, and then a farmer accompanying my father on his preaching journeys, I would again be a missionary, briefly a footballer, and later a farmer. So, I wrote poems and drew apocalyptic pictures to describe the breadth of ways. Art can be a method; or a methodical way to make parts of the whole from one place. It is clear to me now, that in the unknowing of childhood, creativity and individuality are attempts to make tangible the notion that life ahead could be a natural, or a spiritual way'

In his foreword to the exhibition, the critic, Ron Skibbard declared:

“These paintings make no attempt to inspire with subliminal imagery but are concerned with language, the surface language of paint. He presents us with an image of the sea, or an image inspired from the Bible. In effect we are presented with a blank canvas, a space in or on which to act - to create. Here is the sea, here is a relic of Christianity that has shaped our culture ... here is nothing, nothing more than a painting. The painting of religious relics is in acknowledgement of the currently largely discredited patriarchal system, but they seek to recover the humility of belief - to acknowledge the privacy of faith by making the paintings flat and upfront, literally in your face. The surface nature of the paintings, the way they are painted, defies getting lost in them.’

In a small spiral bound notebook (Jon preferred these to sketchbooks – a bundle of five costing £1.00 from a local shop), I discovered that Jon had scribbled the following: ‘the way to paint a religious painting like a Madonna and child has been lost. This is because we have lost the way the Madonna and child were. It couldn’t be the same because it wouldn’t be the same thing. It went so far and then stopped. All things pass’. Was Jon lamenting that passing? Though he moved on from using overt religious imagery it continued to be an oblique presence in his work.

I believe that Jon’s experiences with PAW impacted on his own development and practice. Jon had a hands-on approach to all he did – when working with others he was perfectly at ease and never disturbed when children put hands in paint, on themselves and on him. Paint is a physical material; it has weight and viscosity, texture and smell, taste even. He encouraged a natural and immediate response to the medium. When it came to mark-making, the use of tools was good, but so was the use of hands, feet and bodies. The range of approaches to making work that Jon and his creative collaborators experimented with were many. Some were methodical in their mark making, others were more impulsive; there were, drippers, daubers, pourers and squeezers of paint from pots, all these methods were tried because they were all valid responses to being presented with paint and with colour.

I think that these shared approaches and experiences shaped Jon and his practice too. He became even more open to the possibilities inherent in materials and experimental in his approach to making. This article focuses on his painting practice, but he also experimented with reformed plastic sculpture, crayon rubbings, filmmaking, found material etc. On one occasion, with a group of young adults with Prada Willi syndrome, two cars were cut in half using angle grinders and re-assembled in the gallery (‘Write Off’ Claremont Basement Gallery 2005)

Hello hallo 1997 Oil on Canvas 121.5 x 122 cm Courtesy of Kate Adams

In his statement for 'Under Painting' at St Bartholomew's Church. Brighton in May of 2000 Jon asserted that:

'Painting has always been about joy and about sorrow. The Paintings are an investigation of how appearance is influenced by the addition and subtraction of colour. Painting is a form of representation and the result of accretion. Or. The outcome of an attempt to paint single, flat objects which have an illusory appearance, and which may function as immotive areas in space. What becomes apparent is dependent on that space as an idea. Painting for me is somewhere between a bird and a fly'.

That last sentence of Jon’s has long fascinated and perplexed me. Can painting be bird-like or fly-like? Or both? Painting may be one of the ways that a natural or spiritual course might be steered, and complete liberty might be discovered. Jon wrote: ‘Sometimes making painting makes you feel like a special person’. Birds embody freedom, joy and optimism, the delight of not being caged or constrained. Jon felt harried by the constraints of finding his way in a world where he struggled with belief and with liberty. Impending ecological disaster oppressed him and he sometimes railed against his powerlessness to make a difference. Was painting that necessary thing that provided liberty or moments of freedom? What was at stake in the opportunity to be able to bring forth the thing as its creator? Being in the presence of a painting or sculptural object or a natural thing might be freeing too, perhaps.

Fly 1997 size and whereabouts unknown

And, painting as a ‘fly’? You might say that they’re irritating but necessary. As they get nearer, they get louder and when they do it is hard to focus on anything else. But, just in case you didn’t realise that the painting ‘fly’ is a painting of a fly, Jon has added 3 letters to the head F.L.Y. So, the smeared yellow ochre upside down ‘v’ on a vermillion ground is the annoying but necessary subject. Vermillion, a colour so loved by Titian, a painter so loved by Jon. Is this painting an imagined zoomed in window on the ‘fly on robe spoiler’ of a renaissance painting. Perfection is spoiled or rather imperfection is the reality. Even when paintings appear to be just perfect. Flies remind us of the real present, unless we swat them.

Bird or fly, the act of painting becomes a necessary passage of flight and the act of looking can move you in that freedom direction too. Painting and paintings can preoccupy; you have to labour and work, push through the difficult bits, the failures the restarts. This process can apply to looking too. Sometimes you have to work hard to look with fresh eyes – with eyes that actually see. What you see you might not like but can give you a buzz and maybe force a change of position.

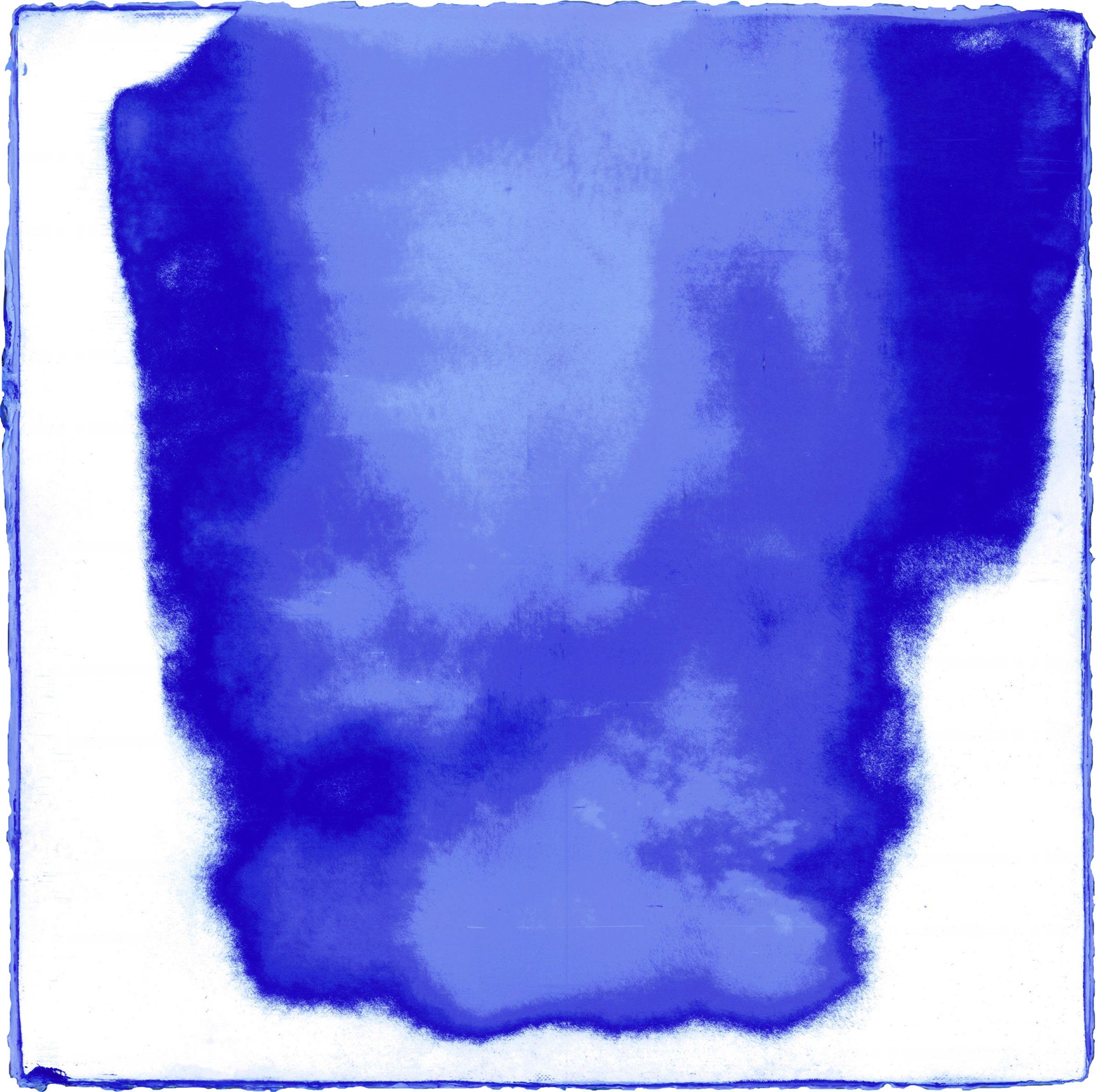

Jesus Blue 1999 Acrylic on board 40 x 28 cm Courtesy of the artists estate

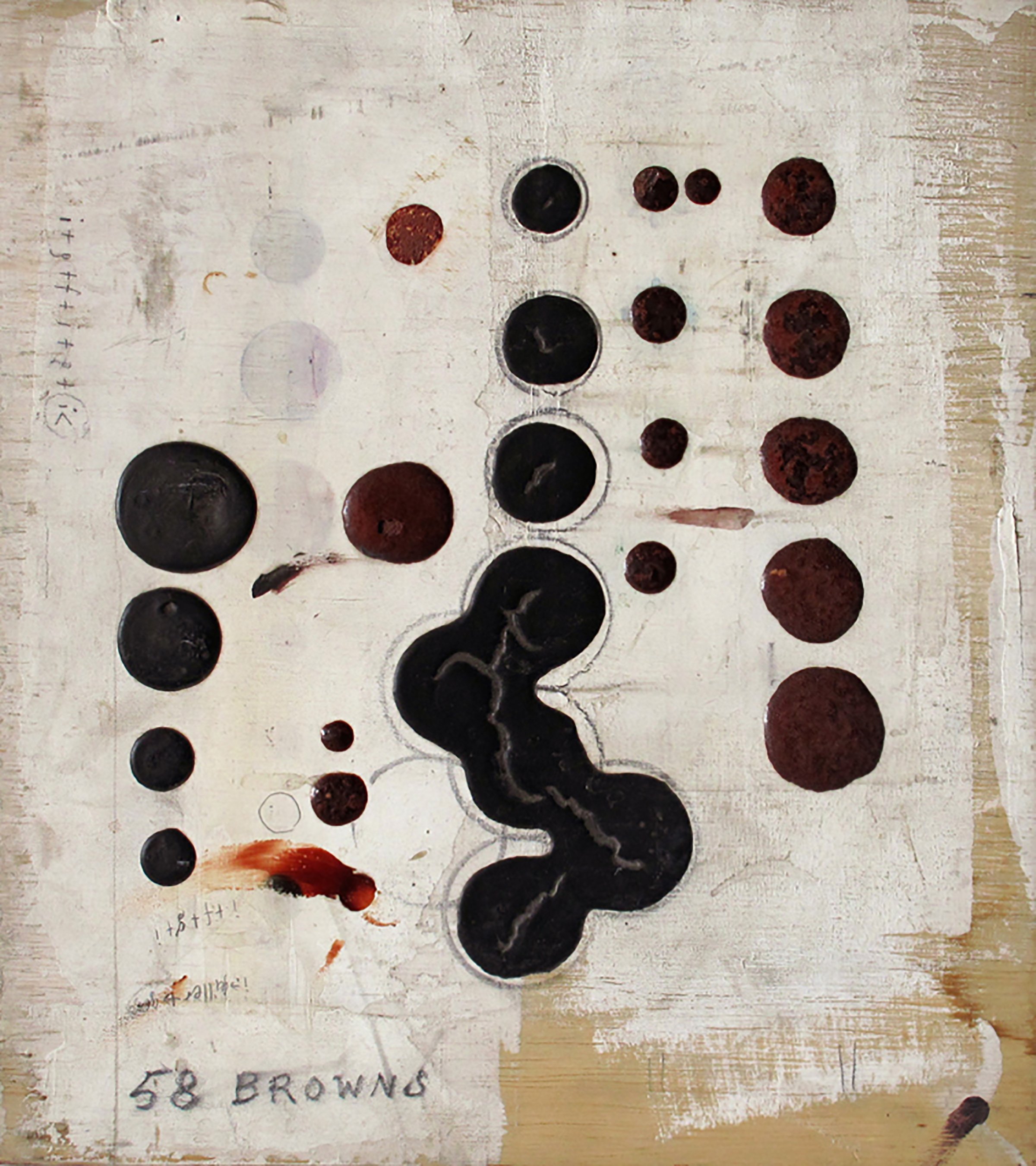

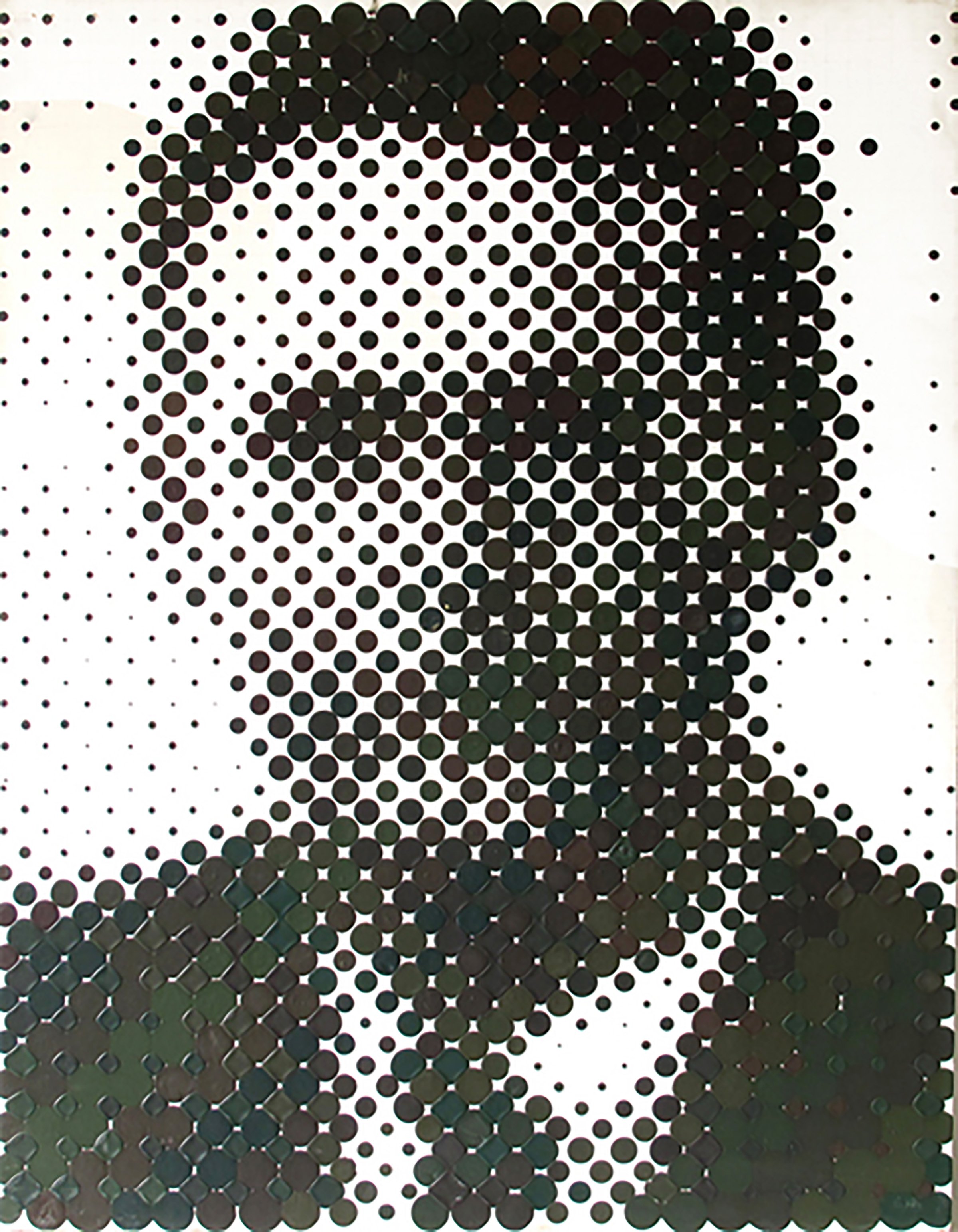

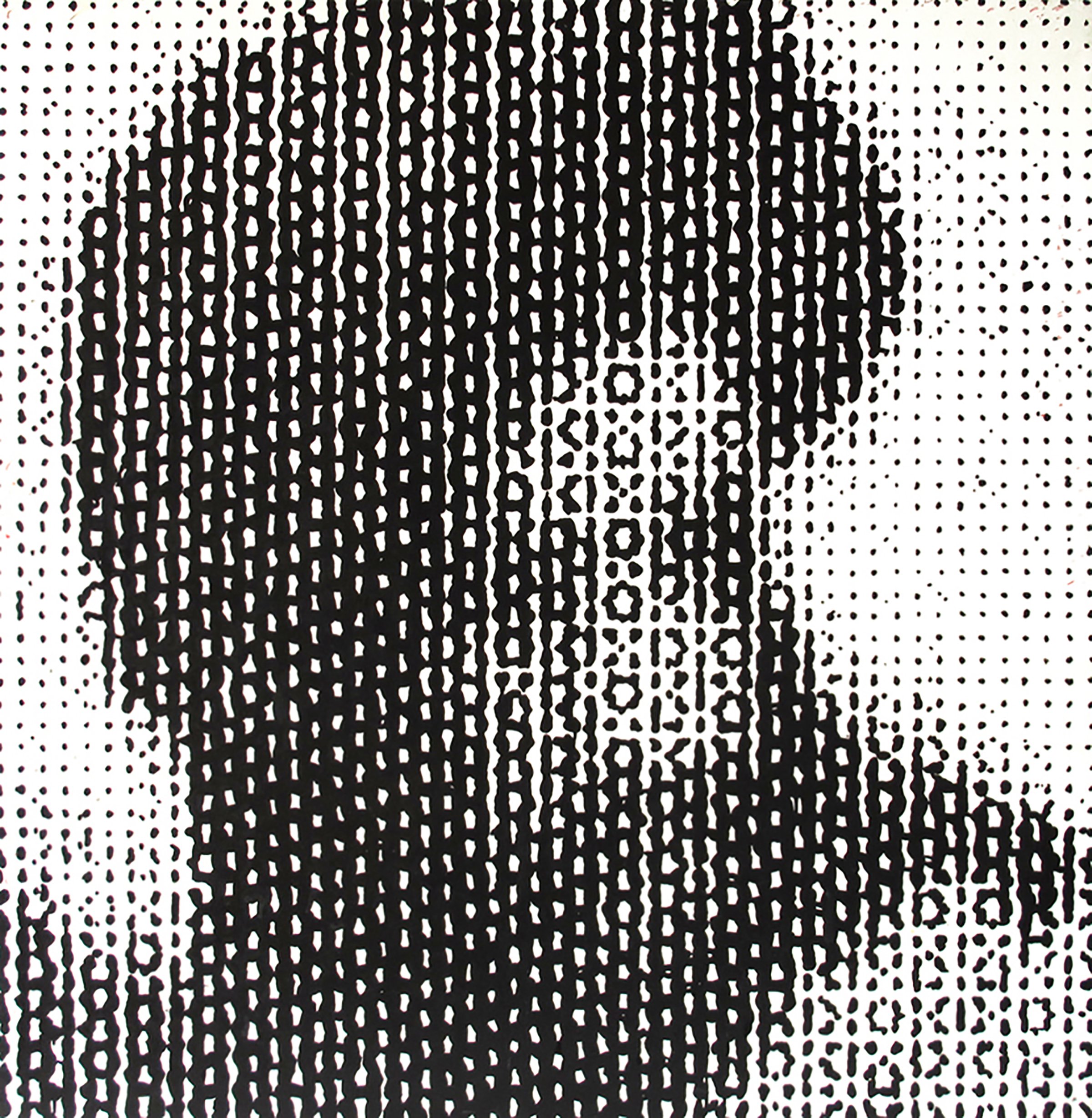

Jon always kept innovating. He experimented with compositions of dots that he placed on canvas or on ply board. Some of these he left (as in 58 browns/test palette) at other times he painted over these raised spherical paint dabs with other coloured layers. Another approach was to build up layers and then sand back these raised dots using an orbital sander. This is the process used in the ‘Memory’ and in ‘The Third Man’ paintings

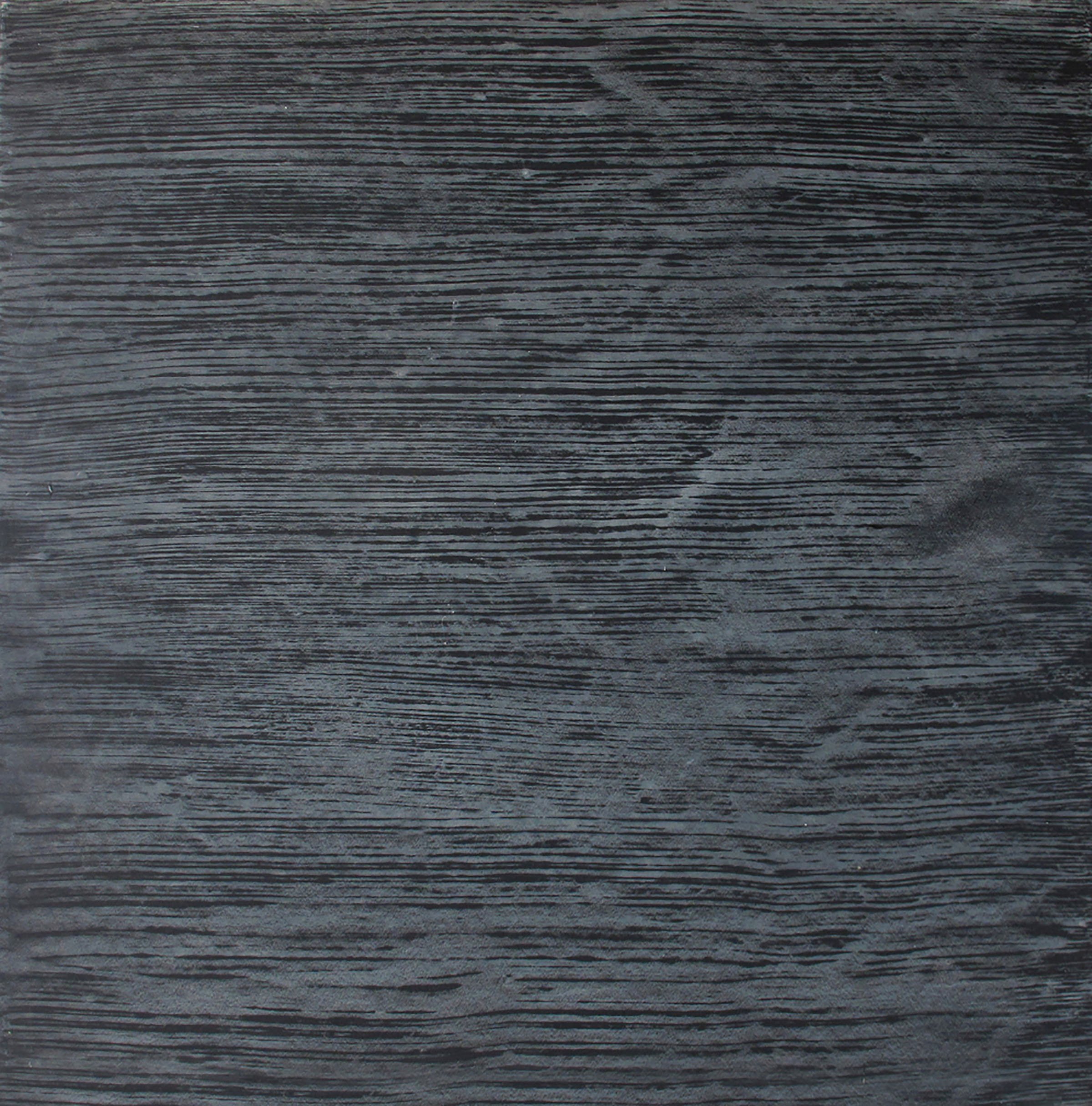

His completed colour field paintings of this period were characterised by sublime smooth surfaces with edges that were replete with accretions of the various paint layers that had been pulled across the work. His mantra; 1. ‘Back to skin’ 2. Three ‘cloaks’. 3. ‘Rub down’. 4. ‘Fresh lick’. 5 ‘Scrape in’. These works I find profound – they are all surface and yet they are also lesson’s about depth in painting.

Jon still potently influences my own practice to this day.

Jon’s final show ‘Coleshow’ at The Arches, Hastings (2006) consisted of 11 large paintings and a composite work, ‘Brown Clown’ installed over the entrance gates. The paintings as a group together are particularly significant as there are so many strong autobiographical and deeply personal references.

Bromley North 2005 Oil on canvas 133 x 167 cm Courtesy of Caroline LeBreton

‘Bromley North’ is a painting that located a moment in time when he was beaten up outside the Churchill Theatre in Bromley High Street. The oblique lines and angles reference the corner of the theatre with its hard-edged silver-grey concrete façade … like all these final works the painting was paired down to significant markers that reference the spot of the experience, in this case a brutal one. ‘Orchard Road’ another location in Bromley references the upright slatted veranda of our family home. The wooden veranda was the portal to the leafy green garden of our youth and celebrates less complicated and happier times.

Orchard Road 2005 Oil on canvas 167 x 133 cm Courtesy of Caroline LeBreton

The Paintings ‘Sticky’ and ‘Untitled (tree)’ are abstract but imbued with figuration and religious overtones. The motif of leafless trees, shorn and reduced to their bare essentials, hovering free from the uniform-coloured ground. Three resolute silhouettes, upright but slanted; testimony to the inanimate forces that shaped their angled growth, and … a voice, a tree in the wilderness bearing witness to who or what will come after. Once more, a recurring reference to the Baptist and concerns of a future climax.

Jon wrote:

'Painting is an idea. It is this idea of belief; that painting might provide a lucid passage through life, and pictures themselves may be a vehicle; to provide room for belief'.

Bird or fly? Belief or Non-Belief – neither, and both – and Doubt? Always.

As usual, Rod expresses my own feelings succinctly:

‘I think his paintings are great, he certainly was’.

Sticky 2006 Oil on canvas 167 x 133 cm Courtesy of Tim Corrigan

At the age of 44, too young, Jonathan Cole was killed in an accident in Cambodia. You can discover more about his life and work on this website and you can find its spirit in the unique approach shared by Kate Adams, Caroline LeBreton, Tim Corrigan and the many artists who have worked with Project Art Works since its inception and, of course, in the remarkable work of its creative collaborators who have been so deservedly shortlisted for the Turner Prize, 2021.

Philip Cole